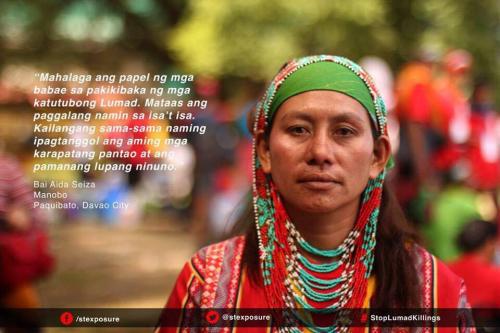

"The role of women in the struggle of the Lumad is important. We respect each other. United, we need to defend our rights and our ancestral land." – Bai Aida Seisa, Bagobo, Paquibato, Davao City

"The role of women in the struggle of the Lumad is important. We respect each other. United, we need to defend our rights and our ancestral land." – Bai Aida Seisa, Bagobo, Paquibato, Davao City

Bagoboi Baiii Aida Seisa does not need a loud speaker to address a gathering. She can speak with a clear, modulated voice to make a point, whether in front of a large crowd, at a negotiation table, or at a press conference.

She has been doing it all her life, and she needs to do it, now more than ever, to save her life, that of her tribal community, and their ancestral lands in Paquibato District, Davao City.

She started out as an organizer in her youth, and now at 36, Aida holds many titles: secretary general of the Paquibato District Peasant Alliance (Padipa), secretary general of the Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas (Peasant Movement of the Philippines)iii-Southern Mindanao Region, vice chairperson of the Sabokahan Lumád Women’s group, and also a leader of the peasant women group Amihan.

Her position in these organizations gave her the task to address government officials and state security forces who neglect or abuse their authority, and this made her a target of red-tagging under Philippine Pres. Benigno Aquino’s counterinsurgency program Oplan Bayanihaniv.

Aida is a wife and a mother to three young daughters, and her family also became a target when her house was attacked by the Philippine Army’s 69th infantry soldiers on June 14, 2015, supposedly to serve an arrest warrant for famed New People’s Army commander Leoncio Pitao, or “Kumander Parago.”

But there was no Kumander Parago in her home, only her family and friends celebrating, over food, drinks and videoke. The soldiers’ gunfire came past midnight, and by dawn, three were dead: her uncle Lumád leader Datu Ruben Enlog, Aida’s village mates and friends Randy Carnasa and Oligario Quimbo.

She and her family were able to get out of the house on time. Since then, she has been away from her village, ironically named Paradise Embac.

“We were massacred, we were all massacred as a warning, to make us silent amidst all the injustice, for us to turn our backs on what history has taught us – that we need to defend our lands ourselves. They want it this way because then it would be easier for them to steal our ancestral domain,” Aida said.

The ancestral lands of the Lumád in Davao City is being threatened by 79 mining applications, Aida said, including applications from companies owned by big compradors such as Edwin Tan and Danding Cojuangco, the President’s uncle. Aside from the minerals, the fertile Lumád lands are also being eyed by agribusiness plantations for rubber, banana and palm oilv.

And it seemed that history has repeated itself, because the June 14 massacre was the second one that Aida had survived.

Her father’s daughter

In 1983, Aida was three years old when their home was strafed by soldiers, private guards of a logging company, and the government paramilitary group, CHDF (Civilian Home Defense Force)vi. Their main target was her father, Amado Sandunan, who had led the fight against the Dalisay logging company. But Amado knew butchers do not spare women or children, and he threw them out the window before the assassins’ bullets killed him. Aida, her mother and two baby brothers were saved.

Aida grew up without her father, but his legacy of defending the land was an aspiration she gladly carried on her shoulders. She helped her mother raise her two brothers, and later, became a young organizer.

“When I was 11 years old, I have already experienced working and earning a livelihood so we can survive, so my two brothers can go to school. It is difficult and painful being assigned as the “parent” being the eldest child, so that you and your family can live. It was also difficult for my mother because she cannot speak Bisayavii, and we evacuated to Davao City after the incident…It was painful,” she said.

“I go to school during the day, send my brothers to school and wash our clothes and uniforms after class,” Aida recalled. Still, she was able to join many organizations, such as the League of Filipino Students, during her elementary days. In her teens, she also became a catechist and leader of the Christ the King Church, which further honed her talent in public speaking.

In involving herself in organizations, Aida learned to deal with people with different attitudes, respect others’ opinions, value criticism and self-criticism, and work within a collective. But she always carried herself with respect, confidence and dignity.

“My father instilled in my mind that we should always assert our right because there will be others who will seek to undermine us,” she said.

As a young Bagobo, Aida struggled not just against poverty, but against discrimination, specially in school.

Aida Seisa (middle), with Ata Manobo leader Bai Bibiyaon Ligkayan Bigkay (right) and Michelle Campos (left), daughter of slain Lumad leader Dionel Campos, lead the Manilakbayan 2015 contingent in a protest action in Manila, Philippines.

“When someone ridicules me for being a Lumadviii, I stand my ground and remain proud of where I come from; I am proud to be a Bagobo. I do not hide this and would always dance during school activities, wearing traditional Bagobo clothes. Other students would mock me and say: ‘This person is shameless, she is really thick-skinned’. I remain the same and just as proud of being a Bagobo,” she said.

“We should never be ashamed of being a Lumád,” she had told her brothers, as she now tells her daughters. Her pride comes from knowing that it is the Lumád tribes that have, for centuries, nurtured and protected the richest lands in the country. It is the indigenous peoples who have kept their unity, tradition and cultural identity against the onslaught of the colonizers and oppressors.

During her father’s time, it was also tribal unity that had forced logging out of their ancestral lands. Now, as an organizer, Aida is trying to spread this unity in both Lumád and non-Lumád communities.

“I believe that no one will be an oppressor if no one allows themselves to be oppressed. This is what I believe in and practice, this is the mentality that I teach others,” Aida said.

Death in her home

Aida lamented how a happy evening in June ended in tragedy.

“It is painful to remember that this happened while we were celebrating three birthdays – that of my 12 year-old and nine-year-old daughters, and my husband. The celebration was also for our wedding anniversary, to celebrate 15 years of marriage,” she said.

She said she even borrowed a TV from her neighbor for their videoke singing, since her own TV was too small. Her guests had already downed three gallons of tuba, and feasted on chicken and goat meat. They were drunk and singing.

At past midnight, three groups of soldiers started firing at her house.

They ducked for cover, but Randy Carnasa had been shot, twice. He pleaded with her to escape while she still can, to tell people the truth.

Aida and her husband Henry carried the dying Carnasa out of the house in the hope that neighbours would see and rescue him. Then, they ran to the forest with their 12-year-old daughter, who was also shot in the arm.

The next day, soldiers claimed it was “a legitimate encounter,” and that the three killed were rebels.

“The water that we boiled for the goat meat was the one they used to pour on Datu Ruben Enlog, my uncle. This was why some parts of his body were scalded. The kettle was found on his side, and he was dragged from the house. They were all inside the house, they were shot there, but the soldiers dragged them outside to make it seem that they fought back, that there was an armed encounter; they even planted guns to make it seem that way. Randy, however, it was us that brought him near the side of the road. We carried him, me and my husband, because we were hoping that when the sun comes up, someone would pass by the road and see him, and help him. He was still alive by then, but the soldiers found him and finished him off. They used the bolo that belonged to Datu Ruben Enlog; they used it to kill off Randy. He was shot by a gun and killed by a bolo,” Aida recalled.

On June 12, two days before the massacre, the 69th Infantry Battalion of the Philippine Army included Aida among those charged with trumped up cases of frustrated murder in connection to an encounter with the NPA in Calinan District in May. The charges were apparently meant to intimidate Aida as she led a fact-finding mission on military aerial bombings in a nearby village.

She had been branded by the military as a rebel, but Aida attested that soldiers regularly passed by her house, and casually talk to her.

“While they were roving, they sometimes come by our house and call me ‘nay’ (mother) even though they are older, or even if we look the same age. They ask if they can use the toilet and they always take a long time, probably, because they were scouting the area for NPA because I was being tagged as an NPA. But I try to be civil and still accommodate them. I even gave them coffee when they asked if I had some,” she said.

Grief and joy

She may have been wrought with great pain, but Aida knows that life, like a coin, has two sides. With every hardship comes success, with every tragedy comes great joy.

“Thinking about this is very painful. Thinking about what happened to them is very hurtful, but this has made me more determined. I was challenged to never cease my efforts in organizing and in leading our community. Despite the pains of what happened to me and my family when I was young, up until now that I’m married, I will continue.”

After the June 2015 massacre, Aida came out and testified before a Davao City local government council investigation on the incident. She also filed charges against the military officials before the Office of the City Prosecutor.

She had to leave Paquibato and stay at the Lumád church sanctuary in Davao City, where hundreds of evacuees are staying. Despite all the difficulty and threats on their lives, she saw there the students and teachers, striving to hold classes.

“The unity we have achieved because of all this, this is what makes me happy. It makes me happy when the children make their own initiatives to continue their studies even in the evacuation center. I am happy when the volunteer teachers still continue to teach the children even without salary during their stay in the evacuation center. I am overjoyed that many have showed support for the students who are in evacuation centers. Many groups have helped in supplying the kids with paper, crayons, pencil, and such,” said Aida.

She went to Manila as part of 700-member Manilakbayan 2015 delegation of Lumad, peasants, women and youth from Mindanao and spoke before church gatherings, school forums, and mass actions, in each one she was overwhelmed by the support she received for the call for justice, and the Lumád cause to defend their ancestral lands and the right to self-determination. She saw how the struggle had brought together women, men, and the youth, not only in Southern Mindanao Region, but the whole country, with even the support of international groups.

Manilakbayan’s campaign triggered even more outpouring of support to the Lumád, specially for the evacuees, and for the tribal schools which had suffered attacks from soldiers and paramilitary groups.

But what makes her specially proud is seeing how her own family had shown unity and strength in the face of the attempt on their lives.

“We did not falter, instead, many were more determined to continue fighting for the cause that we’re fighting for. Because of what the military did to our family, many more of our family members showed their support for they have seen that Aquino, and other previous presidents, have done nothing for the benefit of the Lumád,” Aida said.

She has been more of a fighter and survivor than a victim, and through all the hardships and sacrifice, she has been more happy than sad.

“I am happy seeing our children like this, seeing our children willing to learn and uniting with us in our struggle. They stand with us; the young ones stand alongside the women and men in the community for the protection of our land and rights. Seeing this, I think to myself that our community has a bright future ahead, since our young ones are like this. They are the hope of our nation, and they can steer our future,” she said.

______________________________________

[i] Bagobo refers to one of the largest

indigenous groups occupying Mindanao, and is composed of three sub-groups. The

three sub-groups namely Tagabawa, Clata and Ubo, belong to one socio-linguistic

group, but with minor differences such as dance steps and dialects.

[ii] Bai is a term increasingly used as

reference to women leaders in indigenous communities.

[iii] Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas is an

alliance of farmers spanning regional and provincial chapters nationwide. It is

a democratic and militant movement of landless

peasants, small farmers, farm workers, rural youth and peasant women.

Primarily, it struggles for genuine agrarian reform and national

industrialization amidst a feudal Philippines. See:

[iv] Oplan Bayanihan is the

counterinsurgency program adopted by the Aquino administration. It is a policy

patterned after the 2009 US Counterinsurgency Guide, and has been stated as a

justification for the continuous attacks in Lumad communities. It is hounded by

its medium term goal to render the New People’s Army (NPA) irrelevant on the

first half of its program. Oplan Bayanihan will end in 2017 and it still has

not achieved its goal. Instead, to meet targets and goals, the AFP has attacked

the civilian population in its rampage of killings, threats, and arrests.

[v] A list of mining companies in Davao, as

well as mining applications is provided by the Mines and Geosciences Bureau,

Regional Office. See also:

[vi] The Civilian Home Defense Forces (CHDF) refers to a unit created by

Ferdinand Marcos via Presidential Decree No. 1016 on September 22, 1976. It is

composed of civilian volunteers supposedly for the purpose of expediting peace

and order throughout the country. However, the CHDF became a group synonymous

with militia abuses and brutality. The 1987 Constitution sought to dissolve the

CHDF but was continuously used by the military in its counter-insurgency

operations for several more years. It was ultimately replaced by the Citizen Armed Force Geographical Unit

(CAFGU), which, in comparison to the CHDF, proved to proliferate the same

brutality and abuse.

[vii] Cebuano belongs to the Philippine branch of Malayo-Polynesian languages

and is spoken by about 20 million people in the Philippines. It is spoken

mainly in the Central Visayas by the Bisaya people, and is also spoken in

northeastern parts of Negros Occidental province, in southern parts of Masbate,

in most of Leyte and Southern Leyte, in western portions of Guimaras, in parts

of Samar, Bohol, Luzon, the Biliran islands, and in most parts of Mindanao. It

is used as a lingua franca in the Central Visayas and in parts of Mindanao

[viii] Lumad is a collective term for non-Islamized

indigenous groups in Mindanao. It hails from a Bisayan term meaning “native” or

“indigenous”, and was accepted by about 15 Mindanao ethnic groups to

differentiate themselves from Moros, Christians, and other Mindanao settlers.

—————————————-

This article is part of “Bayi: Herstories of Women Human Rights Defenders in the Philippines,” a publication that will be released by KARAPATAN Alliance for the Advancement of People’s Rights and Tanggol Bayi (Defend Women) on March 2016. This project is supported by the Urgent Action Fund for Women.

Photo credits: Efren Ricalde, STExposure, Christian Yamzon